Anterior Cruciate Ligament injuries are common in sport (Evans and Nielson, 2022) and can occur in a variety of ways, but an individual’s recovery from the injury depends on a number of factors. In this blog we hope to cover the common patterns of ACL injury, other structures in the knee that can be injured, and what to do leading up to surgery to help promote a good recovery.

Finding out that you have injured your ACL can be devastating news for any professional athlete or a fit and active person. Often people are uncertain about what they need to do, how long they are going to be out for, what any imaging they have had means and whether they need surgery or not?

Defining ACL Injuries

Partial ACL Tears

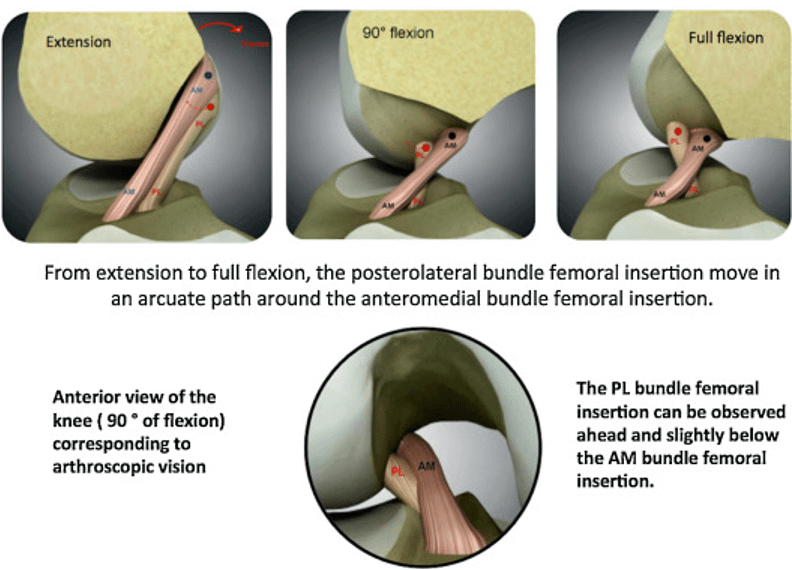

The truth is, when someone is told they have injured their ACL that can mean several things. Firstly, the ACL like all ligaments can be torn to varying degrees. The ACL is divided into 2 bundles, the larger and thicker Postero-lateral bundle (PLB) and the smaller Antero-Medial Bundle (AMB). With the knee straight or extended the PLB prevents the shin bone sliding forward on the thigh bone, but with the knee flexed or bent the AMB prevents the shin bone sliding forward on the thigh bone. Both bundles are very strong and packed full of nerve endings that give feedback to the brain that adjusts the contraction of the muscles around the ACL being stretched. Unfortunately, sometimes the knee is placed in a position where your ACL cannot absorb the forces produced or react quickly enough to the situation with your muscles and injury occurs (Amis and Dawkins, 1991).

The smallest injury that can occur is a single bundle tear which is most commonly the AMB. This is often referred to as a Partial ACL Rupture or Grade I ACL. These can heal without surgery and usually take 3-4 months to get back to play.

Full ACL Tears

A full ACL Tear or ‘Rupture’ as it suggests is where the ACL is completely torn through both bundles leaving you without a functioning ligament to help stabilise the knee during movement.

ACL injuries can either happen during a collision or contact, or non-contact. Over 70% of ACL injuries occur in non-contact situations and there are 3 common mechanisms of injury:

- Quick deceleration or putting the brakes on

- Hyperextension when the knee is forced backwards or locks out

- When pivoting or twisting with the knee bent

For contact ACL Tears there are 2 common mechanisms:

- The foot is fixed in a tackle causing the sudden deceleration of the leg

- A direct contact to the knee or upper shin causing the knee to lock out on bend and twist

Alongside these mechanisms are more subjective signs of injury these include:

- Reaching out for the knee with your hands whilst falling

- Loud cries of pain

- Staying still and not moving until medical attention arrives

Finally, physical signs that the injury has occurred are:

- Large swollen knee or Hemarthrosis

- Inability to weight bear on the leg

- Feeling unstable when putting weight through the knee

- An inability to fully bend or straighten the knee.

If your injury is like this and you have a large swollen knee, you really do need to get, preferably someone with sports experience or significant musculoskeletal experience to assess you and help guide what you need to do next…

Diagnosis

Once the injury has occurred most people will find it difficult to weight bear on the knee due to pain and swelling and may end up in A+E. They will usually have a check x-ray to rule out a bony fracture around the knee joint (this is particularly pertinent in our younger athletes 9-16, who may pull a plug of bone out of the shin bone rather than rupture their ACL). Usually, they are given crutches and basic advice on swelling management and asked to contact their GP practice. GP’s and other professionals such as physiotherapists and nurse practitioners may suspect an ACL injury and consider an MRI scan. In some areas you may be booked in the next day to Orthopaedic Clinic where they may decide to do an MRI quickly although this is rare.

An MRI scan pictures all the other tissues around the knee, not just bones but muscles, ligaments, tendons, joint capsule, cartilage, meniscus (shock absorbers) or bursa (fluid filled sacks). The scan for most people will usually take a couple of weeks to occur and a further couple of weeks for the report to be completed and returned to the GP practice, so be prepared to wait for it.

For Professional Athletes they are usually imaged privately the next day and pay a premium for a fast report.

Associated injuries, are all ACL injuries the same?

Depending on how you injured your ACL, if it was landing from a jump, twisting, and pivoting, or slowing down after fast movement, a number of different structures can be involved. Whilst all ‘ACL injuries’ are referred to under this umbrella term, very rarely do you injure your ACL in isolation. It will depend on what structures you have injured and what the medical team feel they need to repair, which can affect the amount of time you will need to allow the knee to calm down before progressing rehabilitation.

Here is a list of potential injuries and combinations that are referred to as ACL injuries:

ACL Bundular Tear

ACL Rupture

ACL Rupture with Medial Meniscus Tear

ACL Rupture with lateral Meniscus Tear

ACL Rupture with Medial Collateral Ligament Injury (Sprain or Rupture)

ACL Rupture with Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury (Sprain or Rupture)

ACL Rupture with Knee Capsule Tear (RAMP Lesion)

ACL Rupture with Medial Meniscus and Medial Collateral Tear

ACL Rupture with Lateral Meniscus and Lateral Collateral Tear

ACL Rupture with Postero-lateral Corner Injury (PLC)

ACL Rupture with Postero-medial corner injuries (PMC)

ACL Rupture with PCL Injury (Sprain or Rutpure)

ACL Rupture with Cartilage damage (Osteochondral defect)

Combinations of these injuries mentioned can involve to a greater or lesser degree of these structures. The most significant ACL injury I have ever seen involved an ACL Rupture, tears to both the medial and lateral meniscus, a moderate grade MCL injury and bone bruising to the top of the shin bone. Therefore no 2 ACL injuries are alike, and the umbrella term of ACL injury makes communicating how the different structures involved will affect the speed at which rehabilitation can progress vitally important. People often hear that the average time for returning to play is 9 months but it’s just that an average with the range being somewhere from 7-14 months.

How do these associated injuries change rehabilitation?

For the greater majority of those who have an ACL + associated injuries and wish to return to sports that involve change of direction, pivoting or landing on one leg from a height (most invasion sports such as football, netball, rugby, hockey) different combinations of injuries impact what the surgeon will need to do to make the knee stable. A stable knee is the minimum platform required for a successful rehabilitation of the knee.

Bundler or Low-grade ACL tears often require just rehabilitation, although in high performance athletes, if a surgeon is not sure they may do a surgery to look inside the knee (Arthroscope) to confirm this.

ACL Ruptures with no associated injuries can be treated with or without surgery especially if there is no desire to return to invasion sports.

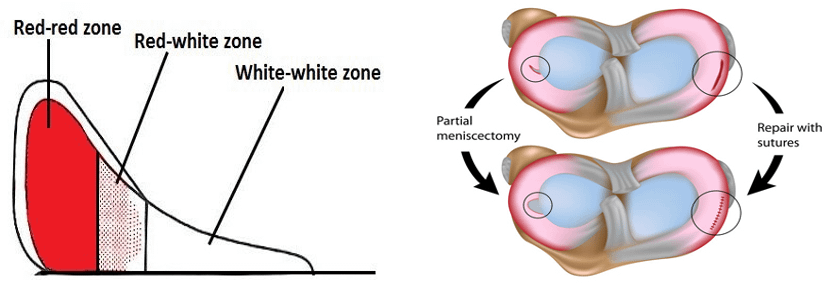

An ACL Rupture with associated meniscal tears can either be removed or repaired. The meniscus is divided into a white zone which has no blood supply and a red zone with a blood supply. Tears to the white zone are generally removed which is called a partial meniscectomy. This leaves the majority of the meniscus to function normally again and depending on the size of the part removed, this can lead to an increased risk of developing arthritis of the knee later in life. On the plus side rehabilitation can begin straight away as normal.

Damage within the red zone or in a younger athlete (15-25) where preserving the white zone of the meniscus is deemed important then the meniscus is repaired using stitches. This leaves the whole surface of the meniscus in situ providing good shock absorbing force. This will usually require a period of non-weightbearing after surgery to allow the meniscus to heal, this may impact the initial stages of rehabilitation as learning to walk again takes a little longer but will not slow down the overall rehabilitation.

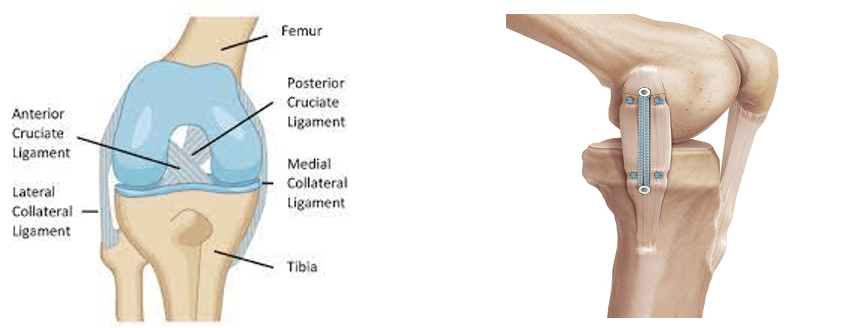

With Collateral Ligament Injuries, Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) on the inside of the knee or Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) on the outside of the knee, the severity of injury will guide treatment. Grade 1 injuries, small tear, will be allowed to heal on their own. Grade 2 injuries where up to 50% of the ligament torn, will require bracing and a limited range of movement in that brace for a period. It will also require limited weightbearing which can affect the initial progression of rehabilitation. Finally Grade 3 injuries where the ligament is ruptured same as the ACL are now also being repaired with several surgeons developing an internal cage technique. This has become preferred in the last 2-3 years after several athletes complaining of instability on the inside of the knee during the rehabilitation process. LCL injuries are rare and often require a surgical repair.

RAMP lesion or capsular tears only occur at the back of the medial meniscus where the meniscus and the knee joint capsule attach to each other. They need to be identified and, in all cases, repaired as leaving RAMP lesions increase the likelihood of future ACL and meniscus injury. The knee may need to be braced with restrictions of movement to help the knee heal impacting the start of rehabilitation but often has no long-term effect on the speed of recovery if rehabilitation is followed.

Injuries that involve more than 2 structures such as: ACL, meniscus and collateral; ACL with PLC or PMC or ACL and PCL rupture simultaneously are really complex injuries that need careful consideration. You and your surgeon will discuss the best possible outcome but because of the amount of structures involved, these rehabilitations are often longer than the commonly thought 6-9 months and are usually 12+ months for full rehabilitation.

Osteochondral Defects (OCD) are where the piece of cartilage and bone from the joint surfaces is broken off leaving a fragment in the knee joint. Osteochondral Lesions (OCL) is where just the cartilage is damaged not the underlying bone. This, if left, usually causes pain and instability. There are a number of ways to treat both these injuries from; replacing the fragment and surgically re-attaching it to the joint surface through to microfracture where small holes are drilled into the area to release blood and create a healing environment where new cartilage is formed over the injured area. You and your surgeon will discuss the preferred technique for how to treat these injuries. A procedure like this will also affect the overall healing time and push the rehabilitation timeframe more towards 12 months.

ACL Surgery

There are several different ways a surgeon can repair your ACL after rupture. The 2 most popular are your hamstring and your patella tendon.

Your hamstring is usually taken from the same knee and taken from the hamstrings on the inside of your knee leaving a scar on the inside and top of the shin. A patella tendon graft is taken from the bottom of your kneecap leaving a scar just below your kneecap to the top of your shin bone. Finally a Quadriceps Tendon is a more recent technique where a slip from the thigh muscle tendon above the knee is taken to form a new ACL. There is no scientific consensus of one graft being superior to another in overall rehabilitation and a number of factors will be considered in discussion with you and your surgeon. To give an example of this from sport, you may be an athlete that is very fast and use your speed or agility as a key attribute for your performance, this may mean you have had hamstring injuries in the past due to this. In this scenario a surgeon may decide not to take a hamstring graft but use a patella or quadricep tendon graft to protect your key sporting attribute.

Prehabilitation

Unless you’re a professional athlete you are unlikely to have a surgery acutely and often there is a period of time to wait for surgery. In this time it’s really important to get the knee functioning normally again before surgery. This involves restoring normal range of movement, eradicating swelling and getting the thigh muscles as strong as possible. If you are lucky to have had some previous measurements of strength and size of muscle this can be a guide. If not you can use scores from the uninjured side as a guide. Find yourself an experienced clinician who is used to treating ACL repairs who can take the correct measurements and get you a good plan in place.

The evidence base is overwhelmingly in favour of prehabilitation. It has a positive effect on your recovery from surgery and long-term participation in sports (Cuncha et al, 2022).

Rehabilitation is not robotic its an individualised journey.

Having considered all the different types of ‘ACL injury’ and the different types of surgery, the most important part of the rehabilitation process is the individual, age, gender, injury history, personality, pain tolerance, muscle physiology, muscle strength, muscle power and overall fitness. These all have an impact on how quickly we recover and those in better condition pre-operatively usually recover quicker and better (hence why we advocate prehabilitation).

Add this to the type of injury you have had, the surgical procedure and the potential post-operative protocols you need to follow. These injuries are unique for every individual and need to be treated as so. It’s important that you and your therapist set goals and use a structured pathway for rehabilitation with you only progressing when you hit certain markers for muscle strength or control in certain movements, not just using time as a marker. Going back unprepared for sporting activities is a recipe for disaster and taking the time to allow your knee to fully recover is the most important thing.

At Pure Physio Sports we use a Gateway Rehabilitation Protocol that uses physical markers for you to achieve before you progress in your rehabilitation, not time. This ensures you make an appropriate recovery for your sporting activities, and it gives you the confidence that when the time is right you will be physically and psychologically ready to return to play.

Our Southern Clinical Lead Chris Hedges will be doing a series of blogs on this topic laying out the basic milestones for ACL rehabilitation in the early, middle and end stages of rehabilitation.

References

Amis AA, Dawkins GP. Functional anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament. Fibre bundle actions releated to ligament replacements and injuries. JBJS. Vol 73-B.(2) 1991. p 260-267

Cunha J, Solomon DJ. ACL Prehabilitation Improves Postoperative Strength and Motion and Return to Sport in Athletes. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022 Jan 28;4(1):e65-e69. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.11.001. PMID: 35141537; PMCID: PMC8811524.

Evans J, Nielson Jl. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injuries. [Updated 2022 May 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499848/

Howell M, Liao Q, Gee CW. Surgical Management of Osteochondral Defects of the Knee: An Educational Review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2021 Feb;14(1):60-66. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09685-1. Epub 2021 Feb 15. PMID: 33587261; PMCID: PMC7930143.

Thoma LM, Grindem H, Logerstedt D, Axe M, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA, Snyder-Mackler L. Coper Classification Early After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture Changes With Progressive Neuromuscular and Strength Training and Is Associated With 2-Year Success: The Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohort Study. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Mar;47(4):807-814.

https://www.thesteadmanclinic.com/patient-education/knee/microfracture-technique#:~:text=Microfracture%20is%20a%20surgical%20technique,way%20down%20to%20the%20bone. Accessed 15/12/2022

https://www.orthobullets.com/knee-and-sports/12736/posteromedial-corner-injury Accessed 14/12/2022